And here is the final part of my book. I am really pleased with a lot of what's in this part (if I say so myself), though there are a few things I would like to change, including one bit that I don't think works at all. If you've made it this far and would like to let me know what you think, you can leave a comment or email me via the contact form. Maybe one day you'll get to see this with pictures and world bubbles? We can but dream.

Part 5 – Spring 1969

Scene 1

Moscow

Rudolf Barshai is getting ready to leave his apartment. He puts on a scarf and picks up his bag. He opens his door. A postman is outside. He looks up and hands Barshai two pieces of mail.

Postman: Comrade Barshai.

Rudolf Barshai: Thank you.

Barshai opens the first letter, which reads:

“In response to the request of 14th January, the District Union of Workers has decided that Comrade Barshai has no need for a telephone”

RB: No need! My mistake.

The second letter is a telegram, which reads:

“Rudolf Borisovich, please ring me as soon as possible! D Shostakovich”

RB leaves his building, heads to a call box. He has to wait. When his turn comes, he dials the number.

RB: Dmitri Dmitrievich, this is Barshai.

DS: Rudolf Borisovich! This is most urgent. How many percussionists do you have in your orchestra?

RB: Err… two, but we find more when necessary.

DS: Very good. Wonderful! This is very important information for me.

RB: Can I ask what you are working…

RB starts, but there is *click*. DS has hung up.

Later, RB is on the podium, in front of the Moscow Chamber Orchestra.

RB: We’ll pick it up from there after lunch.

Assistant: Rudolf Borisovich, telegram for you.

RB opens the telegram, which reads:

“Rudolf Borisovich – please ring me most urgently! D Shostakovich”

RB is next seen on the phone.

DS: How many double basses can you get?

RB: As many as you need.

DS: Excellent! Thank you.

He hangs up. RB hangs up, again a little confused. The phone then rings. He answers.

DS: Rudolf Borisovich?

RB: Here.

DS: I have too much to ask you! What’s the earliest you could see me?

Scene 2

The Town of Zhukovka, near Moscow.

RB steps off a bus on a leafy street, carrying a folder in his hand. Around him are the signs of spring: he wears a coat, but there are buds and leaves on the trees. He walks along a wide track lined with rough trees and bushes. A cat walks in front of him; he reaches down to stroke its head. He then comes to a wooden house. He looks at the house, then checks a piece of paper with an address on it. He looks around. While he has his back turned to the house, Irina Shostakovich appears at the front door.

IS: Rudolf Borisovich!

RB: Irina Antonovna!

IS: Won’t you come in? Mitya’s so looking forward to seeing you.

RB: Of course. I don’t suppose you know what he’s up to?

IS: He’ll explain everything.

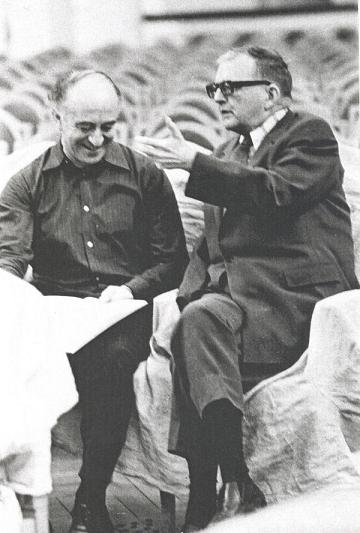

They enter the house. DS is sitting with Kirill Kondrashin, who leaps up and strides over to RB.

KK: Rudik!

RB: Kirya – good to see you! I didn’t know you were involved with this.

KK: I’m not. The honour falls elsewhere this time, my old friend.

DS is trying to stand, with great effort.

RB: Dmitri Dmitrievich, please don’t worry…

IS: Mitya.

DS: I’m fine! Thank you so much for coming.

RB: It’s an honour to be invited.

IS: Mitya, a drink for the occasion?

DS: Go ahead, please! But I’d better stick to my prescription.

KK: What’s that?

DS: Water.

Irina is getting glasses and pouring vodka, which she hands around.

RB: What’s the occasion?

DS: Well, the birth of something special. I do think this one is very special, actually.

KK: A landmark.

DS: Thank you, Kirill Petrovich! (to RB) Did you get the poems?

RB: I did. Quite a journey, though, I think you omitted the title?

DS: I’ve finally settled on Symphony No 14.

KK: Isn’t it wonderful? We’ve waited with baited breath, Rudik!

RB: Well I’ll drink to that.

They drink. RB then gestures to a large book on the table.

RB: And is this it?

DS sits back down.

DS: Mm. Doesn’t look much, like that, but in there are the darkest things I could dream.

RB: The verses were… astonishing.

DS: They still chill me. All those poets were young. They didn’t see old age.

KK: Well I’m eager to hear it. This seems something very new.

DS: I really don’t think I’ve written anything to equal it. My whole life has been moving towards this point. I thought at one time that my best music belonged to my youth, but here we are.

RB: Is the premiere arranged?

DS: Hardly. I’ve yet to ask the conductor!

RB: Who is it to be?

DS: I’m really hoping that you will do me the honour.

RB: Are you… serious?

DS: Oh, but if it’s not…

RB: It would be the greatest honour of my life.

DS: Thank goodness! I’ve rather fallen in love with your wonderful chamber orchestra.

RB: I only hope I can do it some justice.

DS: You are younger than me. But you know the truth of what it says. I’m sure of it. I know you were only a boy, but you remember that time. (He looks at Irina) Youth couldn’t hide any of us from that.

A pause.

RB: I must say I’m dying to have a closer look at the score…

DS: Don’t worry, Rudolf Borisovich. We’re alone.

RB: Yes… alright. I suppose one looks for a way out of talking about… that sort of thing.

DS: I know. I do. I’ve spent a lifetime avoiding tricky subjects. When I was young, I let them talk me out of writing tricky music. I suppose it was the sin of wanting to live. But I’m not young now. While I can see, and hear, and put the pen on the paper, I want to address this… end that is waiting for all of us. I want to tell everyone that they’re not alone, that we’ve all seen it and lived with it. Will you help me, Rudolf Borisovich?

RB: There’s no question.

DS: I’m so very grateful. You recall what Apollinaire says? “The day is dying, see how a lamp/ is burning in the prison./ We are alone in my cell,/ fair light, beloved reason.” Let us be the lamp.

DS starts to stand again.

DS: I’d really like to play the symphony for you.

Irina and Barshai move to steady him.

DS: Don’t worry! I’m alright.

Scene 3

Outside the Zhukovka dacha. Kondrashin is walking with Barshai, and waving back to Irina, who is stood in the door of the house. They walk away up the track towards the road. Some time passes between them before either speaks.

RB: This is all… unexpected.

KK: What were you expecting?

RB: I don’t know. To give some advice.

KK: He doesn’t need advice. He doesn’t take it, anyway!

RB: Well I can happily comment on matters of orchestral texture. But what this symphony says – I can barely take it in.

KK: That’s why he writes this stuff down – so there’s at least a blueprint. But you and I – we only need to understand so much.

RB: Were you hurt? That he didn’t choose you?

KK: Not at all. I had my holy scripture. And Melodiya were good enough to issue the Gospel According to Kirill Petrovich on long-playing record.

RB: I don’t know if I’m ready to be an apostle.

KK: It’s like he said. This country made you ready.

RB: I’ll have to approach Khrennikov.

KK: Details. Khrennikov can foul up your plans, if he pleases, but you’ll come through. This is a gift, one we are uncommonly lucky to have been granted. It will live on when you and I are just footnotes in a book or names on a record sleeve.

Scene 4

In Tikhon Khrennikov’s office. Khrennikov sits behind a large desk. Barshai is on the other side, lower than Khrennikov. Khrennikov is reading some papers. There is silence. Eventually:

Tikhon Khrennikov: This is not ideal. These texts and their subjects are… unfortunate.

RB: I think it’s a very important work. Very deeply felt, very serious.

TK: That may be. This is Lenin’s anniversary year. Perhaps Comrade Shostakovich has forgotten…

RB: … I don’t think there’s anything wrong with Dmitri Dmitrievich’s memory…

TK: … and after his good sense with the symphonic poem October, it would have been expected that he might produce something more in the spirit of this time of celebration.

RB: Should you decide to refuse permission then…

TK: Refuse? Refuse? We are not in the business of censorship, Rudolf Borisovich.

RB: I have been advised that space at the Conservatoire might be…

TK: Despite what you might think, allocation of performance and rehearsal space is not a simple matter.

RB: But this is Shostakovich we’re talking about.

TK: (after a pause, in which TK leans forward in his chair) We are talking about complicated arrangements. At the very least, we will require an audition for the symphony, in order to be certain that scheduling it for public performance does not have… unfortunate consequences for anyone involved.

RB: And then you’ll authorise a premiere?

TK: I’m sure I needn’t remind you that the Union of Composers does not allow or prevent anyone’s music being heard. It is simply the responsibility of the composer in question to ensure that their work is fit for public consumption.

Scene 5

At DS’s Moscow apartment. Irina is on the phone. As she speaks, DS appears behind her, looking somewhat worried.

IS: Did he give you a date? That’s a pity. I’ll pass that on. Mitya’s very worried about the score – are they nearly finished with it? ... Oh. Well, we’ll see you next week then, Rudolf Borisovich. ... And to you.

DS is now in the next room, looking at a game of patience laid out on the table.

IS: Barshai says Khrennikov’s demanding a run-through. (There’s no response) Mitya?

Irina gets up and approaches DS, who’s standing at the table. She looks round him at the cards on the table.

IS: The 3 on the 4?

DS: Uh… I looked right through that. I can barely think!

IS: You mustn’t worry. The score will be back in no time.

DS: Maybe you’ve more faith in copyists than I do. No one ever saw the score of the 4th Symphony again. They had to stich it all together again from the parts.

IS: Barshai says they’re nearly done with it.

DS: Barshai?

IS: Yes, he was just on the phone.

DS: You didn’t say.

IS: Mitya, I have letters to write.

Irina goes back to the other room. DS goes to the piano and picks out a tune with one hand. Irina is sorting papers when there’s a knock at the door. It’s Isaak Glikman.

IS: Issak Davidovich! This is an unexpected pleasure.

IG: Irina! Yes, I arrived a day early and wanted to come straight over.

IS: He’ll be glad of the distraction. Me too. He’s worried sick about them losing his symphony.

IG: Well, I’ve news from Kozintsev on King Lear. Might take his mind off it.

Irina takes Glikman’s coat. Glikman goes to the door of the room in which DS is poking at the piano. He waits a moment.

IG: Give me a few more notes – I’m sure I’ll have the tune.

DS spins around.

DS: Issak Davidovich! I thought you were…

IG: Tomorrow. Yes. I came early. I hope you don’t mind.

DS: Just as long as you’re not hiding any well-wishers.

IG: I think I shook them at the station. Listen, Dmitri Dmitrievich, I have some news of Grigori Kozintsev.

DS: There’s too little time for well-wishers.

IG: Kozintsev?

DS: Oh? How is he?

IG: Alright. No younger. Working on Lear.

DS: Does he want me?

IG: You are his first choice.

DS: How can I commit? Is he close to shooting?

IG: He’s…

DS: I might die before they ever play my symphony. How can I think about film music?

IG: He’d just like to talk some things over.

DS: I don’t have the capacity… I keep playing the symphony, again and again. Maybe it won’t fall out of my head then. If they lose it, maybe I can write it out again. But if I die, what then? No score, no composer? What if I go? I wait to be taken in the night, but you don’t know when! That particular visitor doesn’t do the courtesy of knocking on the front door.

IG: Alright. No plans. Kozintsev will wait. But I don’t think talking about tomorrow, or next month, or even next year will make them less likely to happen. I’ll leave this with Irina Antonovna, and if you want to look, then that’s up to you.

Glikman steps out of the room to see Irina.

IG: He’s in a state.

IS: I know. It’s hard to see him like this. It’s getting hard.

There’s a knock at the door.

IS: Now who could that…

Irina opens the door. It’s Maxim and his young son Dmitri.

IS: Maxim! How good to see you! And little Mitya too!

Little Mitya: Hello Irina Antonovna.

IS: What excellent manners!

MS: I think they skipped my generation - apologies for not phoning ahead.

IS: You wouldn’t have got through – it’s barely stopped.

MS: And Isaak Davidovich! This is a fine little reunion.

IG: We seem to be called together at such moments.

DS joins them in the hall.

Little Mitya: Dedushka!

DS: Maxim! And little Mitya! Are you scoring lots of goals for me?

Little Mitya: Some. But I like being in goal.

DS: Good. That was my position, once upon a time.

DS pats little Mitya on the head.

DS: A fine lad. What a fine lad.

IS: Won’t you come and have some tea?

As the visitors head into the apartment, DS turns to Glikman:

DS: You know, when I see little Mitya, I remember that when I’m gone, I won’t really be gone!

Scene 6

At a rehearsal for the 14th Symphony. Barshai is conducting the Moscow Chamber Orchestra in a large rehearsal room. DS and Irina are sitting behind.

IS: Rudolf Borisovich says the run-through is confirmed for 21st June.

DS: It’ll be heard at least once, then!

IS: The first of many, Mitya.

Barshai is seen conducting the orchestra. DS is captivated. Barshai stops the orchestra, and a hand is seen prodding him sharply in the back. He looks around with real surprise. DS is grinning, standing behind him.

DS: Keep going! I never imagined it would sound this good!

Scene 7

At the Shostakovichs’ Moscow apartment. DS is standing, looking at the front door. He looks down at some papers he is holding. He then rubs his face, and has an anguished expression.

DS: Is there time for patience? No. I’d have a drink, if only Dr Ilizarov hadn’t been quite so firm about it.

DS puts down the papers and picks up a tie. Putting it around his neck, he motions to the paper and says:

DS: Did you have a look my notes?

IS: I did. There are some powerful things there.

DS: Hopefully it’ll convince one or two sceptics to humour me for an hour or so, just as long as I don’t lose my voice.

DS fumbles with his tie.

IS: Here.

Irina comes to tie it for him.

DS: Oh it isn’t usually this bad!

IS: Mm, though this is a particularly special one.

DS: It is, you know. I think it’s my best. I think it might also be my last.

IS: You’ve said that before.

DS: I feel I might not have any choice in it this time.

IS: You’ve said that before too!

Irina straightens his tie and buttons his jacket.

DS: Irischka, what would our lives have been like if we could have met when we were both young?

IS: Well, you’d have been able to tie your own tie and there’d have been nothing for me to do!

DS: You might have had a family of your own.

IS: Mitya, you’re my family.

DS Smile gently.

IS: Now, come on. Let’s go and hear it.

Scene 8

The Small Hall of the Moscow Conservatory. We see DS sitting, looking anxious.

IS: It’s alright Mitya. There are friends all around.

DS looks surprised. He turns and sees Aram Khachaturian.

AK: We wouldn’t miss this, my old friend!

Slava Rostropovich and Galina Vishnevskaya are beside Khachaturian.

GV: Hello Dmitri Dmitrievich!

IS: Did you see Maxim over there?

Maxim waves.

IS: And look, Kirill Kondrashin. And Grigori Kozintsev too.

Kondrashin and Kozintsev wave.

Further away, Khrennikov is sitting with Pavel Apostolov.

Khrennikov: Who’s he talking to now? Pavel, can you see? I can’t see.

Apostolov: No… I can’t…

At that moment, Barshai walks on to the stage, bows, and gestures to DS. DS stands, turns sideways, and speaks to the audience. He is holding a folded piece of paper in his hand.

DS: We… We are going to rehearse my... my 14th Symphony.

Audience member: Is that Shostakovich speaking?

Audience member 2: Shush! I can’t hear what he’s saying!

DS: I would like to say a few words about this piece. Err… there are 11 poems. I’m not going to read them – I read out badly – but this is the gist

Khrennikov:

What’s the matter with you?

Apostolov: I don’t feel so good.

DS: The first two are by Federico Garcia Lorca. De profundis is about the very severe and threatening calm that you find in graveyards, then Malaguena, a Spanish dance, happens at a tavern where there are drunken fights. Knives are drawn and death comes in and reaps his bloody harvest. After this are six poems by Guillaume Apollinaire. Lorelei lives for love, but is a sentenced by judges and a bishop to imprisonment in a convent. But she escapes and falls into the Rhine where she imagines that her beloved is waiting for her. After this comes The Suicide, about the suffering and torments of a man who takes his own life. In On Watch, a bullet catches up with a soldier. His beloved has a premonition about it. The next poem seems to be about the same woman, who hysterically mourns her lost love. The seventh poem, also by Apollinaire, is a noble and decent protest against injustice.

The next poem is by Wilhelm Kuchelbecker, the Russian Decembrist poet. It’s a message to his friend Delvig, about the beauty of many things: creative work, the struggle for great ideals, and friendship. Oh, and I forgot: Before that, there is a is the letter from the Zaporozhian Cossacks to the Sultan of Constantinople, which expresses great outrage and hatred towards everything that is evil, base, dirty and repulsive. The penultimate poem grieves for a great poet who had just passed away, and this little poem tells us that death is lying in wait for us everywhere.

You are probably wondering why it should be that I have suddenly decided to devote so much attention to such a cruel and terrible phenomenon as death. These things play on the mind. I am not so old, I suppose, but I feel the shells are falling closer and closer to me and taking with them friends and dear ones.

We see Ivan Sollertinsky.

And all this reminds me constantly of those words of Nikolai Ostrovsky, that life is given to you only once and it needs to be lived honestly, beautifully in every respect and in such a way as to not do anything shameful.

We see Nina Shostakovich, with DS half in the frame.

When writing this symphony, I thought of the death of Boris Godunov: When Godunov is finished off, a moment of lightness seems to set in. This comes, I think from religious beliefs, which I do not share: though life may be bad, when you died everything would be alright, and you could expect complete peace in the next world. Death terrifies me, because I see nothing beyond it.

We see a number of the Babi Yar Jews.

I myself feel closer to Mussorgsky, whose cycle Songs and Dances of Death is a great protest against death and a reminder that one should live one’s life honestly, nobly and decently and never do anything bad. For, alas, it will be a long time before our scientists figure out immortality, and death awaits us all. I see nothing good about such an end to our lives.

We see Irina as a child, with her parents.

We are going to play the symphony now, and I must ask you to be very quiet as we wish to record it to see what problems there are. I am sorry for this.

DS sits down. He smiles to Irina and takes her hand. Then, he waves to Barshai, who is ready to start on the stage.

Barshai conducts. The bass sings the first song. Then, we see Apostolov in the audience, who is looking very ill.

Khrennikov: What has got into you!?

Apostolov suddenly stands, clutching his chest with a pained expression on his face and bulging eyes. He reaches the aisle, and staggers for the exit. There are gasps and mutterings from the audience. The performance continues. In the hall foyer, Apostolov falls to his knees, and then lands face-down on the floor. He is dead. As he falls and dies, we see the performance come to an end in the hall, with strings scrubbing and Barshai’s wide eyes in close-up. His hand is raised. There is silence. DS’s head drops in seeming exhaustion. Then there is great applause. DS rises to his feet and moves slowly to the stage. He goes onstage and bows. When he returns, he thanks some people as he passes them. His attention is drawn to a developing crowd at the back of the hall.

DS: Ira, what’s going on at the back?

IS: Isaak says it’s Pavel Apostolov. He had a heart attack! He’s dead!

DS: What?! Oh, no, no. That’s not what I wanted. Not at all. My goodness.

IS: It’s not your fault.

DS: I didn’t ask for this! Can’t we talk about death without being dogged by it?

In the foyer, amid a crowd, Apostolov’s covered body is being taken away on a stretcher.

On one page, we see a number of Shostakovich’s relatives and friends, and each is speaking about what they have just heard.

Maxim is speaking to his wife:

Maxim: My God. Do you think the music did that? He hounded father, you know.

Grigory Kozintsev is speaking to an unseen companion:

Kozintsev: There were so many images in there. I suppose that’s the film-maker’s curse! But I need time to work through it all.

Kondrashin is speaking to a companion:

Kondrashin: His way with humour amazes me. How did do it, in this of all pieces?

Companion: I’m sure I heard some dancing skeletons!

Kondrashin: Exactly!

Galina Vishnevskaya is speaking to Mstislav Rostropovich:

Vishnevskaya: It’s all so unspeakably tragic. But true, no? I can barely wait to sing it.

DS is being congratulated by members of the audience. Irina handy back. Glikman and Irina speak:

IG: I haven’t had the pleasure of seeing this one being created.

IS: You see the bits and pieces, but you can’t imagine what it is until, well, now.

IG: It’s beyond our comprehension, yes. I think he’s made a mighty tombstone. But it isn’t impassive. It grips me and forbids me to blink. And where ever I go, I’ll carry it with me. It’s for all those who don’t have a grave of their own, I think.

IS: Now they have this.

IG: Let’s hope it lasts and very long time.

IS: Mm. I’m sorry, Isaak Davidovich. My head is swimming with many things.

IG: It’s alright. It takes a lot of strength, to be this close to the flame.

IS: It’s not that. I’m just overwhelmed by thoughts… and memories.

IG: There’s much to say. But maybe, away from so many burning ears.

DS is standing in the crowd, and is approached by Khachaturian.

AK: Dmitri Dmitrievich! Remarkable. I’m awed and shaken, in equal measure.

DS: Thank you, Aram Il’yich, Thank you!

Just then, some other people approach, congratulating DS. He thanks them. When the leave, AK leans in.

AK: What do you see when you imagine death?

DS: Well, I, er…

AK: We’ve seen him, you and I! Although not for…

He abruptly straightens and smiles and more people pass nearby.

AK: … Yes Dmitri Dmitrievich! We must speak more about the orchestration.

As the people pass away, AK leans back in, conspiratorially:

AK: What I mean to say is: He had a face. We saw him, you and I, and I might have thought him immortal, had I not seen his open casket.

More well-wishers

pass, and when they’ve gone, DS realises that AK has vanished. Irina meets him.

IS: I can go and bring the car round now, unless you want to stay? Are you alone?

DS: Aram Khachaturian and I were just reminiscing, but he’s gone. Is… Apostolov still out there?

IS: I saw an ambulance, but...

DS: I think I’d just like to go home now. I’ve summoned something and I’d like to slip out before it sees me.

Irina takes DS’s hand and they smile to each other. We see Glikman, standing apart and looking on at them. He has a melancholy expression.

Scene 9

Outside the hall. DS gets into the waiting car. IG is already waiting inside. Barshai comes out to see him off. Kondrashin is there also. Barshai speaks briefly to Irina.

RB: Is he happy, do you think?

IS: He is very happy, but tired.

RB: I’m so thrilled.

IS: He’ll be in touch, soon.

Irina gets into the front of the car, and Barshai and Kondrashin wave it off.

Kondrashin: Good job, Rudik. Good job.

Scene 10

In the car.

IG: There’s another of your wonderful symphonies in the world. Will you have a drink to celebrate?

DS: I mustn’t. And they might still refuse permission!

IG: Ach, not now. Every writer and musician in Moscow was there.

IS: And many asked me to pass on their congratulations.

DS: They’re all too kind, of course.

IG: Anyway, there’s no way our esteemed colleagues at the Composer’s Union will want to spread the rumour that your symphonies are fatal for officials!

DS: Please. Don’t even joke about it.

IG: I’m sorry. But I did tell you there’d be surprises to come.

DS: I surprised myself most of all! I’d so convinced myself I’d go before hearing the thing that I can barely believe I’m still here.

IS: Well I think we should have a drink to more surprises. And it’ll count, even if you stick to water.

DS: Good surprises, only. I don’t like the bad sort. No more of those, please.

IG: Of all the people, though. You have to admit there’s certain poetry to it.

DS: No. There is no poetry in death. That’s still a soul that’s gone forever, and it isn’t for me to judge its value. It can strike at any moment. We are never safe. All any of us can do is work, and keep on working, and die with our boots on. That’s important. I mean to live by this rule.

He looks out the

window.

In the morning, I think I might ring Rudolf Borisovich. I’ve an idea I’d like to set some more poems soon. And there’s King Lear to think about.

Pause.

You know what? I think I might have a little drink after all.

The car drives through Moscow.

The end.