|

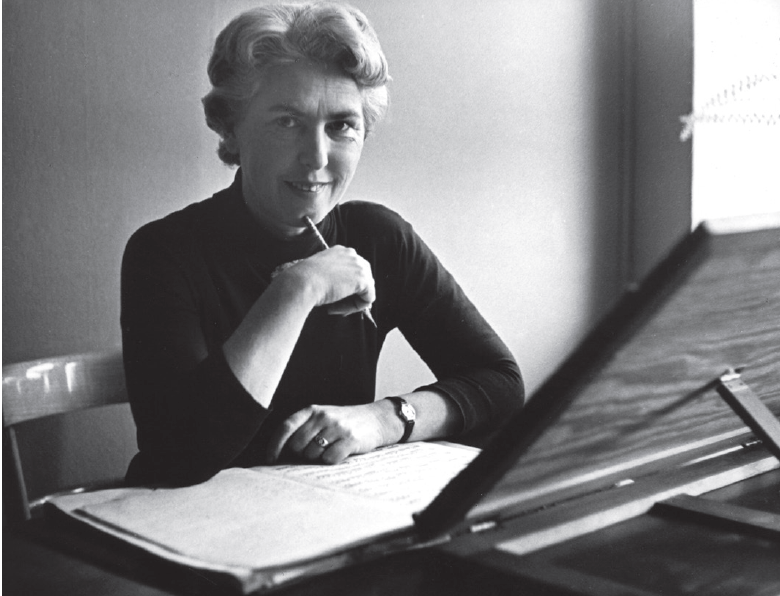

| Helena Dunicz-Niwińska in 1964 (Photo: PWM) |

I'm saddened to hear of the passing of Helena Dunicz-Niwińska, at the age of 102, in Krakow. She was born in Vienna in 1915, and grew up in the then-Polish city of Lwow, where she studied as a violinist. Helena was arrested in 1943 by German occupying forces and deported, with her mother, to Auschwitz. There, her musical abilities saved her from brutal slave labour; instead, she was recruited for one of the camp orchestras, led by Gustav Mahler's niece, Alma Rosé. Rosé was a demanding conductor, but Helena came to understand that her high standards helped keep her and others useful to the Nazi authorities and, crucially, alive. Helena survived the march to Ravensbruck camp in Germany and, after liberation in 1945, settled in Krakow, where she went on to work for the Polish Music Publishers (PWM). She only came to write about her experiences in 2013, and they are related in a book published by the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum.

|

| Helena meeting Pope Francis at Auschwitz in 2016 |

I have a chance this time to visit the bookshop, which reveals the admirable continuing efforts of the State Museum to shine the light of scholarship onto areas still offering fresh perspectives. For obvious reasons, I’m drawn to a recent publication by Helena Dunicz Niwińska called One of the Girls in the Band: The Memoirs of a Violinist from Birkenau. Helena only published these memoirs in 2014, at age 99, and given that she saw the camp through adult eyes (she was 28 when sent to Brikenau in 1943), her account of Auschwitz’s strictures and realities is a particularly direct and prosaic. There’s also the sense of a story being set straight: Helena refers to a few previous published accounts of musical life at Birkenau that fell short of real veracity.

Helena’s account also reveals an undimmed admiration for Alma Rosé, the niece of Gustav Mahler and director of the women’s orchestra (one of a number of ensembles at Birkenau). Rosé did not survive Auschwitz, succumbing to a sudden illness in April 1944, but Helena paints a portrait of a hugely accomplished musician for whom the highest musical standards in the most degrading conditions were a matter of dignity and survival. Rosé worked tirelessly on arrangements of music for the orchestra’s motley assortment of instruments (including lots of violins, mandolins and guitars, but few bass instruments), though much of that work is lost to time, living only in the memories of the few remaining witnesses to this ray of light in a hell on Earth.

Helena’s account also reveals an undimmed admiration for Alma Rosé, the niece of Gustav Mahler and director of the women’s orchestra (one of a number of ensembles at Birkenau). Rosé did not survive Auschwitz, succumbing to a sudden illness in April 1944, but Helena paints a portrait of a hugely accomplished musician for whom the highest musical standards in the most degrading conditions were a matter of dignity and survival. Rosé worked tirelessly on arrangements of music for the orchestra’s motley assortment of instruments (including lots of violins, mandolins and guitars, but few bass instruments), though much of that work is lost to time, living only in the memories of the few remaining witnesses to this ray of light in a hell on Earth.I’m an inveterate botherer of tour guides, and as we wend our way through Birkenau, our expert guide Renata tells me about her friend Helena’s book. I admit to having bought it earlier in the day, given my interest in all things violin. “Well”, she says, “I have something for you”. At the end of the tour, Renata retrieves from her car one of a few remaining discs made recently featuring a reconstruction of music arranged by Alma and pieced together again from Helena’s memory. It’s Chopin’s Etude Op10/3. As a Pole, Chopin’s music was forbidden, but this piece was played only in rehearsal for the enjoyment of the musicians. Rosé’s instrumental ingenuity is here, in the careful use of violins and mandolins and the voice soaring above the bass-light texture. It must have seemed like a warm bath of memory and humanity to those who heard it, a momentary relief from fetid reality. And on this crisp sunny February afternoon, it’s another fleeting connection to the individuals who came to this place and, in most cases, did not leave.

Helena Dunicz Niwińska (1915-2018) died on June 12th. Any images used here fall under "fair use" and are reproduced for the purposes of review and study. They will be removed at the request of the copyright holder(s).