In memory of Gennady Rozhdestvensky (1931-2018), who died one month ago today.

1

Gennady Rozhdestvensky is watching a student closely. The

young conductor in the loose suit clasps the air, and maestro’s onto him. “What

was that gesture with your left hand?” he snaps. “To stop” says the student,

apologetically. “Stop what? A draft? What’s the point of stopping those who

aren’t playing?” Movement is an anathema to Rozhdestvensky’s conducting. Not

show; barely moving can become a show, as he spends a lifetime demonstrating.

But a grand arc of the arms, when a turn of the head or a shrug of the

shoulders will make the point? A waste.

Upon his death, this June, his friend Gerard

McBurney tells the BBC about the habits of Rozhdestvensky’s craft. “He had an

extraordinary gift for conducting the way musicians want conductors to work –

without words. He never talked about the music. He just did everything through

his eyes, his eyebrows, his smile, and his hands and his baton.” And if the

movement tells all, why spend the afternoon labouring the point? “He didn’t

rehearse much and they were all really delighted because they’d knock off early

and go home,” says long-time Rozhdestvensky-watcher David Nice, of the

conductor’s BBC Symphony Orchestra years. “They loved him for that. What he

brought to the actual performance though was something completely different and

inspirational, which hadn’t ever happened in the rehearsal.” His musical

appetite is voracious. Have you ever heard a Russian orchestra play a Vaughan

Williams symphony? Rozhdestvensky recorded them all. A shark must keep moving

through the water in order to breathe, but no more than that.

2

Gennady Rozhdestvensky is old before his time. He is

barely twenty years of age, but his hair is thinning, almost gone. He leads the

Bolshoi in a performance of The

Nutcracker and from this moment on, he will be a conductor of ballet. Where

others will scorn it as menial stickwork, he will take the great scores of the

ballet repertoire to his heart; he will blow the dust from their covers and

dance them with his hands. In the dying days of the Soviet Union, the youthful ballets

of his friend Shostakovich come down from the shelf and move once more: The Golden Age; The Bolt; The Limpid Stream.

Bright jewels from days of possibility, before the scales fell and terror

enveloped all. Rozhdestvensky bears witness to most of the Soviet era, but not

its beginning. His father was there, with the Red Army, putting down the

sailors’ revolt at Kronstadt, near Petrograd, in 1921. His father, Nikolai

Anosov, a conductor. Mikhail Tukhachevsky led the forces of the Bolsheviks that

day, leaving 10,000 rebel bodies strewn across the wreckage and the winter ice.

Tukhachevksy, the patron of Shostakovich during his ballet days. Tukhachevsky,

the name no one dared speak after he was swallowed by Stalin’s purge. Time

passes and the fear recedes, but never completely. The young man learns the

choreography of professional and political survival, but from a comfortable

distance, they’ll ask, as though it were really that simple: “but he wasn’t for the communists, surely?”

3

He crouches, in conference, with his greatest compatriots. The Royal Festival Hall, London, 1960. Mstislav Rostropovich with

his cello and Shostakovich talking around what he really means. “Good! Very

good! But could it be a little quieter?” Two years later, Rozhdestvensky will

bring to the West an earthquake, on paper, in the form of Shostakovich’s

long-dormant Fourth Symphony, put away in more difficult times. And every time

he brings a Soviet orchestra as news of Red culture, Rozhdestvensky will enter

into battle with the bureaucracy, with the swamp of officialdom that doesn’t

know, and doesn’t care, and has its instructions, comrade. Much later, he

recalls, for Bruno Monsaingeon’s film

The

Red Baton, going to an official’s office and being informed that 10% of his

orchestra would not be authorised to travel abroad. Which 10%? Well, that’s to

be decided later. The list, when it arrives, pulls 9 wind players and 3

strings. “You knew you had to plan replacements!” hisses the official.

Rozhdestvensky continues:

“Yes”, I said, “But how can I

explain it? There are nine woodwinds and three strings, but you see, these

people play different songs. Those with bows play one song, and those with

whistles play other songs. Put them all together and you get a symphony. The

bows can maybe be replaced because they basically all do the same thing. As for

the others, I can’t replace them. How can we wave the flag of Soviet art if

songs are missing from the symphony?” His eyes popped out as if he’d discovered

America. He’d obviously never heard an orchestra. Six months later, another

tour, another 12 musicians banned from traveling. But this time it was nine

strings and three woodwinds! I went back to the same functionary. He was

flabbergasted. “What’s wrong now? We hardly touched the whistles! Only three.

We have to eliminate people, that’s our job!”

4

Gennady Rozhdestvensky is surrounded by books. In a

century in which knowledge has burned so easily, he has treasured it, acquiring

so many volumes that he needs a second apartment to house them all. He emerges

from his reading, and he sparkles. “Imagine an amalgam of Sir Thomas Beecham,

Peter Ustinov and Isaiah Berlin,” recalls his agent, Robert Slotover, for the

BBC. “An hour with Gennady Nikolaevich is like a year at university”, comments the

writer Viktor Borovsky. He is sage, but elusive. “He was a bit teasy and

whimsical”, says David Nice of interviewing Rozhdestvensky in the 1990s. “You

thought you’d got very little, but when you played it back you’d got quite a

lot, because he tended to express himself aphoristically.” But he is vulnerable

and ever-so-easily bruised. One afternoon, he sits in his dressing room at the

venue of a west-European orchestra with whom he has had an occasional

association, and notices that his name is not mentioned in the ensemble’s brief

biography. Rage and accusations follow. And this is not the only such outburst.

His face so often settles into a knowing smile, but sometimes the play and the

lightness will fall away.

5

The old order is gone; the new one is not so very

different.

Vladimir Putin reaches out to grasp the hand of the beaming maestro,

the People’s Artist of the USSR, Hero of Socialist Labour and, in 2017, recipient

of the Order of Merit to the Fatherland (1

st Class).

Rozhdestvensky’s walking stick leaves the ground as he turns to the cameras,

hand-in-hand with his president. A month later, he is in the German town of

Gohrisch, leading the Dresden Staatskapelle in a last performance of symphonies

by Shostakovich. There are nerves. Mistakes are made, some very large. But

something remarkable happens during the 15

th Symphony,

Shostakovich’s enigmatic valediction to the form. Where it can seem light and

flippant, the Dresedeners and their octogenarian time traveller draw from it

solemnity and grim conviction. The chilly air of a tomb inhabits this

performance, and it proceeds slowly – very slowly indeed – as though the man on

the podium, a man nearing the end of a long life, is looking back to his friend

whose own life was not nearly long enough, but who lives still for as long as

the notes are ringing. Eventually, the stick goes down, and there’s only quiet.

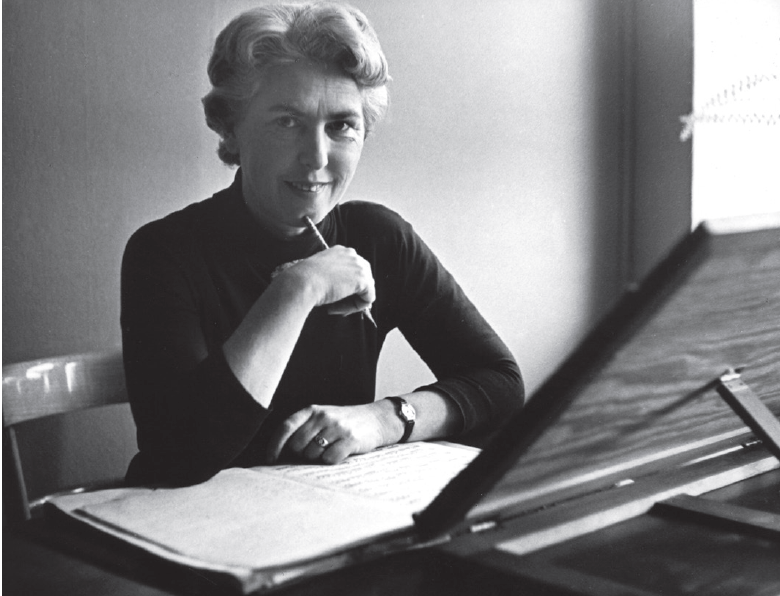

The top image shows Gennady Rozhdestvensky conducting the Dresden Staatskapelle at the 2017 International Shostakovich Days festival in Gohrisch. Image(s) are used under the principle of fair use for the purposes of review and study and will be removed at the request of the copyright holder(s). My thanks for David Nice for his help preparing this piece and to Gerard McBurney and Robert Slotover for giving their permission to quote their tributes to Gennady Rozhdestvesnky.